Tailored approach for lung cancer infiltrating the segmental pulmonary arteries and bronchi beyond the primary involved lobe: a case report

Highlight box

Key findings

• We discuss a tailored approach for left upper lobe lung cancer with metastatic interlobar lymph nodes infiltrating A8, A9+10, and B6. We averted pneumonectomy and opted for upfront double-sleeve lobectomy with complex plasty of the segmental pulmonary arteries and bronchi. This preservation of pulmonary function and overall patient condition provide viable options for post-recurrence therapy.

What is known and what is new?

• Sleeve or double-sleeve lobectomy to avoid pneumonectomy offers better outcomes in terms of preserving pulmonary function and the overall patient condition.

• In the evolving landscape of perioperative strategies, which include molecular targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors, it is crucial to assess the therapeutic options for stage II–III non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cases. Herein, we report a case of NSCLC infiltrating the pulmonary arteries and bronchi of the adjacent lobe.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Complete resection was performed; the lower lobe was preserved via complex plasty of the pulmonary arteries and bronchi. Despite early postoperative recurrence, post-recurrence therapy was promptly administered. Therefore, mastering these techniques may be beneficial for broadening perioperative and post-recurrence therapeutic choices. However, this early recurrence warrants reevaluation of postoperative therapy. Adjuvant chemotherapy alone or chemotherapy followed by immunotherapy may have contributed to better outcomes. We carefully discuss treatment plans for similar cases based on the latest evidence.

Introduction

Background

Various perioperative approaches have been developed for managing locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), such as upfront surgery with adjuvant therapies, induction therapies followed by surgery, and surgery alone (1-3). Furthermore, various evidence supports the perioperative use of molecular targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) (4-9). Therefore, it is vital to assess the therapeutic options for each stage of NSCLC.

Rationale and knowledge gap

When treating centrally located lung cancer or cancer with metastatic interlobar lymph nodes infiltrating the pulmonary artery (PA) or bronchus, avoiding pneumonectomy has a significant impact on the treatment strategy. In recent years, a phase 3 trial demonstrated favorable outcomes for neoadjuvant treatment combining nivolumab and chemotherapy in resectable stage IB to IIIA NSCLC compared with neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone (9). However, concerns exist among some physicians regarding the risks associated with the side effects of ICIs and the potential for inoperability owing to disease progression. Additionally, when the primary lesion or metastatic lymph nodes infiltrate the PA or bronchus, even if neoadjuvant treatment is successful, dissection may be challenging; thus, pneumonectomy or double-sleeve lobectomy may be warranted. Sleeve or double-sleeve lobectomy to avoid pneumonectomy offers better outcomes for pulmonary function and overall patient condition (10,11). In 1999, Okada et al. first reported extended sleeve lobectomy for centrally located NSCLC, which involves the resection of more than one lobe with complex bronchial plasty (11). Since then, cases have accumulated, and recent reports have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of extended sleeve lobectomy compared to pneumonectomy (12,13). This surgical approach also provides additional treatment options for cancer recurrence, allowing for a tailored and potentially effective post-recurrence treatment plan.

No consensus exists on the treatment approach for NSCLC infiltrating segmental pulmonary arteries away from the primary involved lobe. The patient’s tolerance to pneumonectomy, the possibility of avoiding pneumonectomy, and the combination of surgery and perioperative treatment should be considered. The treatment strategy should first be based on specific clinicopathological feature, such as the cancer’s clinical stage, the patient’s general condition and cardiopulmonary function, driver gene mutations and translocations of cancer, expression levels of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), tumor location, and extent of cancer invasion into the hilar structures, and second, on the patient’s preferences.

Objective

Herein, we report a case of complex double-sleeve left upper lobectomy with plasty of the basilar segmental pulmonary arteries and superior subsegmental bronchi in a patient with left upper lobe squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and suspected interlobar lymph node metastasis infiltrating A8, A9+10, and B6. We discuss a tailored approach for this case, including adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatments, surgical procedures, and post-recurrence treatments. Additionally, we discuss a treatment approach for similar cases based on the latest evidence. We present this article in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://shc.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/shc-24-26/rc).

Case presentation

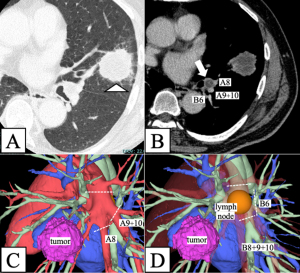

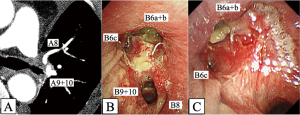

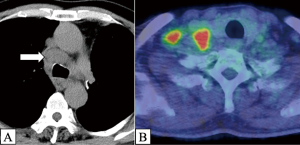

A 57-year-old male, with a history of brain arteriovenous malformation, cerebral hemorrhage, diabetes, and mild paralysis of the left lower limb was referred to our hospital with suspected lung cancer in the left upper lobe. The patient was a current smoker, with a smoking history of 44 pack-years. Computed tomography (CT) revealed a 38-mm solid mass in the left lingular segment (Figure 1A) and an enlarged left interlobar lymph node at level 11L. This node encroaches upon the basilar arteries from the second carina, with suspected metastasis and infiltration into the segmental pulmonary arteries (A8 and A9+10) and bronchus (B6) (Figure 1B). Positron emission tomography (PET)-CT indicated maximum standardized uptake values of 8.9 and 3.7 in the primary tumor and 11L lymph node, respectively. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed no findings suggestive of brain metastasis. Transbronchial lung biopsy of the primary lesion confirmed SCC with 60% expression of tumor proportion score of PD-L1. Pathological diagnosis of the enlarged lymph nodes using endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial fine-needle aspiration was challenging and not accomplished in this case. No lymph nodes were histologically evaluated before surgery, as the CT scan detected no other lymph node swelling aside from 11L lymph node. Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with left upper lobe primary SCC cT2aN1M0, clinical stage IIB. Pulmonary function tests results revealed no ventilation impairment (forced vital capacity: 96% of predicted, forced expiratory volume in 1 s: 2.38 liters, forced expiratory volume in 1 s/forced vital capacity ratio: 73%, and diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide: 91% of predicted). After carefully reviewing the CT findings, which included assessing the extent of the metastatic lymph nodes infiltrating A8, A9+10, and B6, we considered preserving the left lower lobe possible using a complex plasty of the pulmonary arteries and bronchi. Three-dimensional (3D) CT image reconstruction revealed the designated division lines of the pulmonary arteries and bronchi (Figure 1C,1D). Given the lack of evidence of mediastinal lymph node metastasis, we chose an upfront double-sleeve left upper lobectomy followed by adjuvant treatment rather than neoadjuvant therapy followed by surgery after a discussion at the multidisciplinary tumor board (MTB) conference.

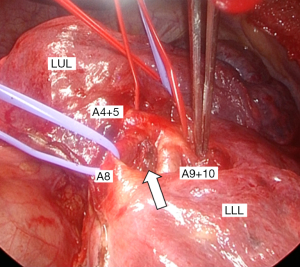

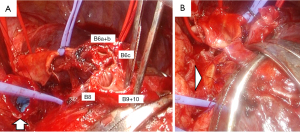

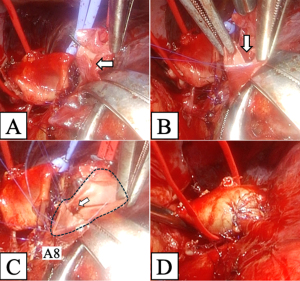

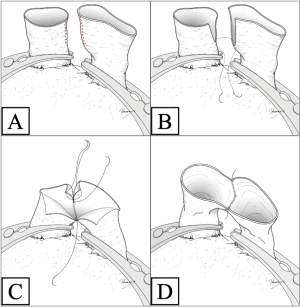

We performed double-sleeve left upper lobectomy with systematic hilar and mediastinal lymphadenectomy via a posterolateral thoracotomy. After confirming the absence of metastasis to the mediastinal lymph nodes via intraoperative pathological examination, left upper lobectomy was initiated. The enlarged interlobar lymph node was fixed to the bronchovascular structures, which supported concerns for suspected metastasis. Dissection of the lymph nodes attached to B6, basilar bronchus, A8, and A9+10 was challenging, indicating possible infiltration (Figure 2). We divided A3 and A1+2a+b by stapling and A1+2c by ligation. We then clamped the main PA, A6, A8, and A9+10, respectively, and ligated A4+5 peripherally to prevent blood backflow from the lingular segment. Subsequently, we incised the proximal PA distal to A6, and then divided the peripheral pulmonary arteries (A8 and A9+10) using Metzenbaum scissors. We then divided the proximal bronchus at the level of the left main bronchus and cut the peripheral bronchi (B6a+b, B6c, and basilar bronchus), completing left upper lobectomy with combined transection of the segmental arteries and bronchi of the left lower lobe. First, we performed a double-barrel anastomosis of B6a+b, with a diameter of 4 mm, and B6c, with a diameter of 3 mm, creating B6 using a running suture with 5-0 absorbable monofilament polydioxanone suture. We then anastomosed the newly formed B6 and the basilar bronchus using the same procedure as described above (Figure 3A). Next, we anastomosed the left main bronchus with the formed lower lobe bronchus, completing bronchial plasty (Figure 3B). Subsequently, pulmonary arterial plasty was performed. We made slits in A8 and A9+10 firstly before anastomosis (Figure 4A,4B) to create a “trunk” of the segmental arteries (Figure 4C) and avert postoperative stenosis of the segmental arteries. After creating a “trunk” of the basilar artery, we anastomosed the central PA with the “trunk”. Using this technique, we completed plasty of the PA (Figure 4D). A schematic image of the procedure for this complex technique is shown in Figure 5. We covered the bronchial anastomotic site with oxidized cellulose gauze, separating the bronchus from the PA to minimize the risk of a bronchoarterial fistula. The surgical duration was 503 min, and blood loss was 300 mL without blood transfusion.

The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged on postoperative day 10. Pathological examination revealed metastasis to the 11L lymph node, infiltration into the surrounding tissue, and left upper lobe SCC with an invasive diameter of 42 mm and no pleural invasion. No additional lymph node metastasis was detected. The pathological stage of the tumor was pT2bN1M0 stage IIB. The biomolecular test detected no driver gene mutations or translocations, including epidermal growth factor receptor mutation and anaplastic lymphoma kinase translocation. Given the pathological diagnosis and the patient’s sufficient recovery from surgical stress, adjuvant immunochemotherapy was deemed necessary for improving the survival outcome. Based on the results of the latest clinical trials, despite repeated explanations of the advantages of adjuvant chemotherapy followed by immunotherapy, the patient refused adjuvant therapy. One month postoperatively, contrast-enhanced CT revealed patency of the PA (Figure 6A). Bronchial patency was also confirmed by bronchoscopy 1 and 2 months after surgery (Figure 6B,6C), and the patient continued to show good recovery.

However, 6 months after surgery, CT revealed obvious enlargement of the subcarinal, bilateral paratracheal, and right supraclavicular lymph nodes (Figure 7A). PET-CT also revealed abnormal accumulation in the same lesions (Figure 7B). Transbronchial needle aspiration revealed SCC of the right paratracheal lymph nodes, confirming postoperative recurrence. Given the patient’s sufficient recovery, we could proceed promptly with concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CRT), cisplatin, and TS-1 (a combination of tegafur, gimeracil, and oteracil) with 60 Gy of radiation, followed by immunotherapy. We completed CRT and subsequently administered two courses of durvalumab without any serious adverse events, and we are continuing with durvalumab.

All the study procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

Opinions from physicians from the hospital receiving the patient

In the present case, we performed an upfront double-sleeve left upper lobectomy for the complete resection of the left upper lobe SCC with metastatic interlobar lymph nodes. Despite lymph node invasion of A8, A9+10, and B6, we managed to preserve the left lower lobe through complex plasty of the segmental arteries and bronchus. Adjuvant therapy was not administered owing to the patient’s refusal. We confirmed recurrence in the subcarinal, bilateral paratracheal, and right supraclavicular lymph nodes 6 months after surgery. The patient demonstrated adequate recovery as pneumonectomy was not performed; thus, concurrent CRT was performed followed by immunotherapy. Considering the occurrence of early postoperative recurrence, our approach warrants further discussion regarding perioperative therapy and surgical procedures.

Considering that the clinical stage of the disease was N1 and we could avoid pneumonectomy through complex arterial and bronchial plasty, we opted for upfront surgery followed by adjuvant therapy. The patient might have tolerated pneumonectomy; however, preserving lung parenchyma was deemed essential for smooth postoperative recovery and timely induction of adjuvant immunochemotherapy. Perioperative treatment strategies for locally advanced NSCLC have been broadly discussed and developed, including molecular targeted therapies and ICIs for neoadjuvant and adjuvant use (4-9). CheckMate 816, an international randomized phase III study, demonstrated that neoadjuvant nivolumab with chemotherapy significantly improved the event-free survival in patients with resectable NSCLC compared with neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone (9). Various studies have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of preoperative ICIs (9,14-19). However, some physicians still express concerns regarding delayed surgery or cancellations of planned procedures due to disease progression or adverse effects, as well as challenges in the dissection of the hilar structures attributed to inflammation and fibrosis. Takada et al. conducted a systematic literature review of published trials investigating neoadjuvant ICIs alone or immunochemotherapy in patients with resectable NSCLC (14). This review included 18 trials and reported surgery cancellation rates ranging from 0% to 45.8%, surgery delay rates ranging from 0% to 31.3%, and conversion rates ranging from 0% to 53.8% from minimally invasive surgery to thoracotomy. Adverse events were the most frequent causes of surgical delays. Notably, the authors showed that adverse events were the least commonly reported cause of surgery cancellations. In contrast, disease progression accounted for 0–75% of surgery cancellations. In cases of disease progression, even if upfront surgery is performed, oncological outcomes may still be poor. Minervini et al. reviewed the literature on surgical complications following preoperative immunotherapy and reported that hilar and mediastinal fibrosis due to neoadjuvant ICIs may result in challenging dissections and a relatively high conversion rate (20). In cases of centrally located NSCLC or metastatic interlobar lymph nodes infiltrating the segmental pulmonary arteries away from the primary involved lobe, avoiding pneumonectomy greatly influences the treatment strategies. Mortality rates and the likelihood of adjuvant therapy failure were higher in patients who underwent pneumonectomy than in those undergoing lobectomy (10,21). Although such tumors respond to neoadjuvant immunotherapy or immunochemotherapy by shrinking, subsequent hilar dissection might be extremely challenging owing to inflammation and fibrosis around the pulmonary arteries. To be clear, it should be noted that in the described trials and literature, R0 resection and surgical completion for patients receiving immunotherapy were equal to or greater than rates in the control/placebo arms. Thus, the concerns regarding the inability to reach surgery or more complex operations based on immunotherapy do not appear to be justified; however, the presence of any systemic therapy continues to add these nuances compared to no induction therapy at all. In our case, due to concerns about missing the opportunity for surgery because of potential adverse events, neoadjuvant immunochemotherapy followed by surgery was considered but ultimately not selected. Regarding neoadjuvant CRT, evidence of survival improvement has not been established, even in patients with cN2 NSCLC (22-28). Furthermore, considering the patient’s history of diabetes, we anticipated grave challenges with post-radiation vascular and bronchial plasty. Therefore, we considered upfront surgery followed by adjuvant therapy.

In this case, complex plasty of the involved segmental pulmonary arteries and bronchi enabled preservation of the left lower lobe and avoided pneumonectomy. Regarding the surgical techniques to avoid pneumonectomy for centrally located lung cancer or metastatic lymph nodes invading the hilar structures, many cases of extended sleeve lobectomy have been reported (11-13). Extended sleeve lobectomy, first reported by Okada et al. in 1999, involves the resection of more than one lobe with complex bronchial plasty and sometimes includes pulmonary arterial plasty (11). The procedure is classified into types A through D depending on the tumor’s location (12). In our case, a type B procedure, which involves combined resection of the upper lobe and superior segment with anastomosis of the left main bronchus and basilar bronchus, could have been applicable. Considering the prolonged operative duration and the risk of anastomotic failure after the complex bronchial reconstruction performed in this case, a type B extended sleeve lobectomy might have been a valuable option. Recent studies support the safety and efficacy of extended sleeve lobectomy. Voltolini et al. demonstrated that extended sleeve lobectomy is a feasible alternative to pneumonectomy, providing similar outcomes in terms of tumor control (12). Additionally, another study showed that complex sleeve lobectomy results in fewer postoperative major complications compared to pneumonectomy, highlighting its advantage in minimizing postoperative risks (13). Toyooka et al. conducted a single-center retrospective study that included 104 patients who underwent neoadjuvant CRT followed by surgery for NSCLC (29). The authors demonstrated that sacrificing the pulmonary arterial branches to the preserved lobe may cause anastomotic complications following the induction of CRT, followed by sleeve lobectomy. Therefore, when performing sleeve or double-sleeve lobectomy after induction therapy, we should carefully consider whether the involved pulmonary arteries can be preserved. In our case, we managed to avoid pneumonectomy and spare the patient’s pulmonary function and general condition through a complex technique involving plasty of the segmental pulmonary arteries and bronchi. For pulmonary arterial anastomosis involving two peripheral separated segmental branches, a simple double-barrel connection of segmental branches is associated with stenosis at the entrance to the segmental branches, where the two segmental branches are connected, and then end-to-end anastomosis is also performed. Conversely, in the technique we used in this case, the peripheral “trunk” composed of the two segmental branches is larger in diameter compared with that made by a double-barrel method and also the entrance to each segmental branches moves away from the end-to-end anastomosis site, reducing the risk of stenosis. Preservation of the left lower lobe potentially allows for more aggressive therapeutic options for managing postoperative recurrence, such as concurrent full-dose CRT.

Considering the early postoperative recurrence in the present case, adjuvant therapy should be administered. Despite sufficient postoperative recovery, the patient refused adjuvant therapy. Whether neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy contributes to the prolonged survival of patients undergoing surgery for NSCLC remains controversial (3,30-35). Generally, the advantages of adjuvant therapy over neoadjuvant therapy include the ability to proceed with surgery promptly following cancer diagnosis and the option to administer longer treatment (35). However, in the adjuvant setting, the proportion of patients who complete chemotherapy is lower than that in the neoadjuvant setting solely owing to a decline in postoperative general conditions or patient preference (31). Recently, the advent of the option of combining ICIs with perioperative chemotherapy has intensified the debate on the combination of surgery and perioperative therapy (8,9). The latest National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend considering preoperative immunochemotherapy for NSCLC with a tumor size of 4 cm or greater, or with positive lymph node metastases, provided there are no contraindications to immunotherapy (36). IMpower010, a prospective randomized phase III trial, demonstrated that adjuvant chemotherapy followed by ICI for patients with resected NSCLC significantly improved disease-free survival compared with chemotherapy alone (9). In the present case, considering that the tumor’s PD-L1 expression was more than 50% and neoadjuvant immunochemotherapy followed by surgery was not pursued, adjuvant chemotherapy followed by ICI should have been administered.

This case report has several limitations. First, as a single case study, the findings may not be generalizable to other patients with similar conditions. Second, the follow-up period was limited, which may affect the long-term outcomes. Third, the perioperative treatments did not follow the international guidelines due to the patient’s refusal. Nevertheless, the technique of complex pulmonary arterial plasty may be considered useful for treating centrally located lung cancer and cancer with metastatic interlobar lymph nodes infiltrating the PA or bronchus. Further case reports and case series on lung cancer infiltrating segmental pulmonary arteries and bronchi away from the primary involved lobe are warranted to pursue a definitive treatment approach.

Several issues regarding the diagnosis and treatment of this patient were further discussed, and further questions were raised, as follows:

Question 1: should we administer neoadjuvant therapy?

Expert opinion 1: Dr. Yoshihisa Shimada

I assume that either neoadjuvant or adjuvant systemic therapy could be effective in controlling systemic disease spread after surgery. However, perioperative systemic therapies are not always effective in preventing postoperative recurrence. In this case, neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy with the CM816 regimen might be beneficial, particularly due to the patient’s high PD-L1 level (60%), which could lead to significant tumor and lymph node shrinkage. If pathological complete response (CR) after surgery is achieved after surgery, it would indicate a high likelihood of long-term survival. While there are risks associated with immune-related adverse events (irAEs) and potential tumor spreads during treatment, chemoimmunotherapy, unlike CRT, generally does not complicate the surgical procedure.

Expert opinion 2: Dr. Mara B. Antonoff

This is a complex consideration; in the current era, neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy would be thought to result in improved cancer survival though may have resulted in a pneumonectomy. Patient social and physical factors must be considered.

Expert opinion 3: Dr. Stefano Bongiolatti

In my opinion, the pre-operative multidisciplinary approach with neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy has some advantages in comparison with the adjuvant treatment and in particular the higher percentage of delivery, the better tolerability, the treatment of micrometastases and the use of pre-surgical period to enhance the patient’s performance (pre-habilitation). Moreover, the neoadjuvant setting permits to avoid unnecessary surgery in patients with early progression. However, every decision should be patient tailored and made by an expert MTB.

Expert opinion 4: Dr. Alberto Lopez-Pastorini

The case presented is interesting not only because of the excellent surgical performance demonstrated, but also because it illustrates the clinical reality in which compromises are commonplace. A patient in whom physicians chose upfront surgery over neoadjuvant immunochemotherapy because of multiple comorbidities. And who ultimately suffers a massive recurrence after refusing adjuvant therapy.

In the described stage IIB, systemic therapy should be administered either in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting. The advantage in terms of overall survival and progression-free survival over no therapy is well established (37,38).

The goal of neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced NSCLC is to downstage the tumor to allow for less extensive surgery or radical resection. In this regard, the aforementioned CheckMate 816 trial showed excellent results with an increased pathologic CR rate from 2.2% to 24.0% in resectable lung cancer for the combination of platinum-based chemotherapy with nivolumab compared to chemotherapy alone (9). In addition, recent studies have shown that sleeve resection after neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy has similar perioperative outcomes compared to sleeve resection alone (39,40). However, there are legitimate concerns regarding the consequences of preoperative therapy, such as difficult dissection due to fibrotic changes, anastomotic complications, and delayed surgery. In the NEOSTAR trial, surgeons felt that 40% of the operations performed after nivolumab or ipilimumab + nivolumab were more difficult than anatomical lobectomies for stage I lung cancer with no prior treatment (41).

In the present case, the surgeons decided to operate upfront for several reasons. The most important was that they had the capabilities to perform a parenchyma-sparing resection in this complex case. Therefore, the question is not only about preoperative therapy, but also about surgical expertise. In centers with less experience with complex sleeve resections, neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy may be a viable option. Whether neoadjuvant therapy would have reduced the complexity of the resection in this case is not certain. Although in some cases lymph node metastases may regress to the point that angioplasty is no longer necessary, in other cases the surgical complexity may increase after pretreatment. Zhang et al. reported a higher rate of pericardial resections and more vascular sleeve resections after neoadjuvant chemotherapy + programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) inhibitors compared to chemotherapy alone, suggesting that chemoimmunotherapy may be associated with more complicated pulmonary resections (42). In conclusion, surgical expertise remains the key factor in this case, highlighting that complicated cases should always be performed in experienced centers.

Question 2: what are the advantages and disadvantages of the surgical procedure, and what skills are needed for the surgery?

Expert opinion 1: Dr. Yoshihisa Shimada

This complex double sleeve technique offers several advantages, including the avoidance of pneumonectomy, preservation of lung function, the creation of a cuff with the PA involving segments A8 and A9+10 to prevent stenosis, and the potential for aggressive treatment after surgery and in the event of recurrence. These benefits, as emphasized by the authors, make this technique particularly valuable. However, there are few disadvantages, such as the complexity of the procedure, which may not be feasible for every thoracic surgeon, and longer operative time required. Achieving this procedure successfully demands tremendous skills and knowledge, including expertise in anastomosis, the selection of appropriate sutures, cramping techniques, anticoagulant therapies, and ensuring proper perfusion after PA anastomosis.

Expert opinion 2: Dr. Mara B. Antonoff

The advantages of this approach are sparing the rest of the lung, though the main disadvantage was the prolonged operative time. This is a complex operation requiring skilled vascular anastomotic techniques from the surgeon as well as support from skilled scrub techs.

Expert opinion 3: Dr. Stefano Bongiolatti

The surgical procedure described is a great challenge and the surgeon should be very skilled because he/she performed three bronchial anastomoses and two vascular anastomoses on a thin and fragile tissues such as segmental arteries and bronchi. The surgical background should be absolutely solid. The pre-operative CT imaging should be implemented with 3D reconstruction to enhance the surgical plans.

Question 3: should we administer adjuvant therapy?

Expert opinion 1: Dr. Yoshihisa Shimada

Since this patient did not receive any systemic therapy for this disease, adjuvant therapy including ICIs could be a better option. However, the decision to proceed with adjuvant therapy should be guided by the patient’s preferences. If the patient chosen not to undergo adjuvant therapy, the decision should be respected, and no adjuvant therapy would be acceptable in this case.

Expert opinion 2: Dr. Mara B. Antonoff

Yes, adjuvant therapy is absolutely indicated in this setting.

Expert opinion 3: Dr. Stefano Bongiolatti

Adjuvant therapy should be mandatory if neoadjuvant therapy was not performed. Moreover, avoiding pneumonectomy, the adjuvant treatment could be effectively delivered to the patients in the right time and with adequate doses.

Question 4: what is the preferred treatment after recurrence?

Expert opinion 1: Dr. Yoshihisa Shimada

Given the recurrent pattern in this patient, CRT would be an appropriate option. Another viable option could be chemoimmunotherapy, particularly due to the patient’s high PD-L1 level.

Expert opinion 2: Dr. Mara B. Antonoff

For recurrence, the preferred approach is chemoradiation followed by immunotherapy.

Expert opinion 3: Dr. Stefano Bongiolatti

As all the oncological treatment, the therapy of recurrence should be patient tailored, based on the international guidelines and also it depends by the site, number of recurrences, biomolecular assessment and by the patient symptoms.

Conclusions

We describe an approach for managing left upper lobe cN1 NSCLC with metastatic interlobar lymph nodes infiltrating the segmental arteries and bronchus of the lower lobe. Our approach of upfront double-sleeve lobectomy with complex plasty of the segmental arteries and bronchus may be feasible, as it avoids pneumonectomy, thus broadening the perioperative and post-recurrence therapeutic options. In this era of emerging perioperative treatments combined with surgery, we believe that this case report will contribute to effective treatment decision making.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Dr. Tomonori Murayama for creating the schematic illustrations.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://shc.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/shc-24-26/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://shc.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/shc-24-26/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://shc.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/shc-24-26/coif). Y.S. serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Shanghai Chest from September 2023 to August 2025. A.L.P. serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Shanghai Chest from October 2023 to September 2025. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work, and ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Research Committee and the Declaration of Helsinki (revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and the accompanying images. A copy of the written consent form is available for review by the journal’s editorial office.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Balmanoukian A, Ettinger DS. Managing the patient with borderline resectable lung cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2010;24:234-41. [PubMed]

- Scherpereel A, Martin E, Brouchet L, et al. Reaching multidisciplinary consensus on the management of non-bulky/non-infiltrative stage IIIA N2 non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2023;177:21-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pu CY, Rodwin S, Nelson B, et al. Approach to Resectable N1 Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: An Analysis of the National Cancer Database. J Surg Res 2021;259:145-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu YL, Tsuboi M, He J, et al. Osimertinib in Resected EGFR-Mutated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1711-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsuboi M, Herbst RS, John T, et al. Overall Survival with Osimertinib in Resected EGFR-Mutated NSCLC. N Engl J Med 2023;389:137-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhong WZ, Chen KN, Chen C, et al. Erlotinib Versus Gemcitabine Plus Cisplatin as Neoadjuvant Treatment of Stage IIIA-N2 EGFR-Mutant Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (EMERGING-CTONG 1103): A Randomized Phase II Study. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:2235-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lv C, Fang W, Wu N, et al. Osimertinib as neoadjuvant therapy in patients with EGFR-mutant resectable stage II-IIIB lung adenocarcinoma (NEOS): A multicenter, single-arm, open-label phase 2b trial. Lung Cancer 2023;178:151-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, et al. Overall survival with adjuvant atezolizumab after chemotherapy in resected stage II-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase III trial. Ann Oncol 2023;34:907-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, et al. Neoadjuvant Nivolumab plus Chemotherapy in Resectable Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2022;386:1973-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ma Z, Dong A, Fan J, et al. Does sleeve lobectomy concomitant with or without pulmonary artery reconstruction (double sleeve) have favorable results for non-small cell lung cancer compared with pneumonectomy? A meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;32:20-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okada M, Tsubota N, Yoshimura M, et al. Extended sleeve lobectomy for lung cancer: the avoidance of pneumonectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1999;118:710-3; discussion 713-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Voltolini L, Gonfiotti A, Viggiano D, et al. Extended sleeve-lobectomy for centrally located locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer is a feasible approach to avoid pneumonectomy. J Thorac Dis 2020;12:4090-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Voltolini L, Viggiano D, Gonfiotti A, et al. Complex Sleeve Lobectomy Has Lower Postoperative Major Complications Than Pneumonectomy in Patients with Centrally Located Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2024;16:261. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takada K, Takamori S, Brunetti L, et al. Impact of Neoadjuvant Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors on Surgery and Perioperative Complications in Patients With Non-small-cell Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review. Clin Lung Cancer 2023;24:581-590.e5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cascone T, Leung CH, Weissferdt A, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus nivolumab with or without ipilimumab in operable non-small cell lung cancer: the phase 2 platform NEOSTAR trial. Nat Med 2023;29:593-604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cascone T, Kar G, Spicer JD, et al. Neoadjuvant Durvalumab Alone or Combined with Novel Immuno-Oncology Agents in Resectable Lung Cancer: The Phase II NeoCOAST Platform Trial. Cancer Discov 2023;13:2394-411. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitsudomi T, Ito H, Okada M, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable non-small-cell lung cancer in Japanese patients from CheckMate 816. Cancer Sci 2024;115:540-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feng Y, Sun W, Zhang J, et al. Neoadjuvant PD-1 inhibitor combines with chemotherapy versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy in resectable squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Thorac Cancer 2022;13:442-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu J, Hou L, E H, et al. Real-world clinical outcomes of neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy in resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2022;165:115-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Minervini F, Kestenholz PB, Kocher GJ, et al. Thoracic surgical challenges after neoadjuvant immunotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer: a narrative review. AME Surg J 2023;3:15. [Crossref]

- Gómez-Caro A, Garcia S, Reguart N, et al. Determining the appropriate sleeve lobectomy versus pneumonectomy ratio in central non-small cell lung cancer patients: an audit of an aggressive policy of pneumonectomy avoidance. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2011;39:352-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thomas M, Rübe C, Hoffknecht P, et al. Effect of preoperative chemoradiation in addition to preoperative chemotherapy: a randomised trial in stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:636-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Albain KS, Swann RS, Rusch VW, et al. Radiotherapy plus chemotherapy with or without surgical resection for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009;374:379-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katakami N, Tada H, Mitsudomi T, et al. A phase 3 study of induction treatment with concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus chemotherapy before surgery in patients with pathologically confirmed N2 stage IIIA nonsmall cell lung cancer (WJTOG9903). Cancer 2012;118:6126-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pless M, Stupp R, Ris HB, et al. Induction chemoradiation in stage IIIA/N2 non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet 2015;386:1049-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Misumi K, Harada H, Tsubokawa N, et al. Clinical benefit of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for the avoidance of pneumonectomy; assessment in 12 consecutive centrally located non-small cell lung cancers. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017;65:392-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen Y, Peng X, Zhou Y, et al. Comparing the benefits of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy for resectable stage III A/N2 non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol 2018;16:8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sinn K, Mosleh B, Steindl A, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy is superior to chemotherapy alone in surgically treated stage III/N2 non-small-cell lung cancer: a retrospective single-center cohort study. ESMO Open 2022;7:100466. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Toyooka S, Soh J, Shien K, et al. Sacrificing the pulmonary arterial branch to the spared lobe is a risk factor of bronchopleural fistula in sleeve lobectomy after chemoradiotherapy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2013;43:568-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- John AO, Ramnath N. Neoadjuvant Versus Adjuvant Systemic Therapy for Early-Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: The Changing Landscape Due to Immunotherapy. Oncologist 2023;28:752-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brandt WS, Yan W, Zhou J, et al. Outcomes after neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy for cT2-4N0-1 non-small cell lung cancer: A propensity-matched analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019;157:743-753.e3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- MacLean M, Luo X, Wang S, et al. Outcomes of neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy in stage 2 and 3 non-small cell lung cancer: an analysis of the National Cancer Database. Oncotarget 2018;9:24470-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lim E, Harris G, Patel A, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemotherapy in patients with resectable non-small cell lung cancer: systematic review and indirect comparison meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:1380-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yendamuri S, Groman A, Miller A, et al. Risk and benefit of neoadjuvant therapy among patients undergoing resection for non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2018;53:656-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Provencio M, Calvo V, Romero A, et al. Treatment Sequencing in Resectable Lung Cancer: The Good and the Bad of Adjuvant Versus Neoadjuvant Therapy. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2022;42:1-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Version 9. 2024. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf

- Douillard JY, Tribodet H, Aubert D, et al. Adjuvant cisplatin and vinorelbine for completely resected non-small cell lung cancer: subgroup analysis of the Lung Adjuvant Cisplatin Evaluation. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:220-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021;398:1344-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dai J, Zhu X, Li D, et al. Sleeve resection after neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy in the treatment of locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2022;11:188-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liang H, Yang C, Gonzalez-Rivas D, et al. Sleeve lobectomy after neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy/chemotherapy for local advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2021;10:143-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sepesi B, Zhou N, William WN Jr, et al. Surgical outcomes after neoadjuvant nivolumab or nivolumab with ipilimumab in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2022;164:1327-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang B, Xiao H, Pu X, et al. A real-world comparison between neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy and chemotherapy alone for resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Med 2023;12:274-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Yuhara S, Kawashima M, Shimada Y, Antonoff MB, Bongiolatti S, Lopez-Pastorini A, Nagano M, Sato M. Tailored approach for lung cancer infiltrating the segmental pulmonary arteries and bronchi beyond the primary involved lobe: a case report. Shanghai Chest 2025;9:2.