Analysis of postoperative outcomes for surgically resected esophageal squamous cell carcinoma reconstructed with gastric conduit

Introduction

Although it is relatively rare disease in Korea, comprising 1.1% among all cancer incidence in 2016 (https://www.cancer.go.kr/lay1/program/S1T211C223/cancer/view.do?cancer_seq=4277&menu_seq=4282), esophageal cancer is the eighth most common cancer and sixth leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide (1). The incidence is increasing rapidly, especially in the Asian belt of the cancer including Turkey, Northeastern of Iran, North and center of China (2).

Esophageal cancer is a particularly lethal malignancy. The reported 5-year survival rates rarely exceed 40% (3). Favorable outcomes are frequently associated with early stages. Although the standard treatment strategies remain ambiguous, surgery is the most suitable choice in early stage disease and the best way to control locally advanced cases (1,4). However, the role of surgery in the treatment of esophageal cancer is somewhat controversial because it is frequently associated with considerable mortality and morbidity rates.

In this study, we aimed to investigate postoperative outcomes after esophageal cancer surgery through a single surgeon’s experiences. We focused on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma because it is the predominant subtype in Asia. The surgical method was confined to Ivor Lewis esophagectomy with gastric conduit with or without laparoscopic conditioning. Because there are various surgical methods available, including conduit conditioning, the method was restricted to avoid bias caused by variations (5).

Methods

The medical records of 223 patients who underwent surgical management for esophageal cancer between 2002 and 2013 in a single institute (Seoul National University Bundang Hospital) were retrospectively reviewed. Among these, a single expert thoracic surgeon (Dr. Jheon) performed the surgeries of 124 patients.

Inclusion criteria were (I) operations performed by the same surgeon (Dr. Jheon), (II) pathology confirmed as squamous cell carcinomas, and (III) use of stomach as a substitute conduit. Patients who were not diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma (8 patients), substitution organs other than stomach (5 patients), transhiatal surgical methods, or comorbid hypopharyngeal cancer were excluded.

Perioperative results and postoperative outcomes including complications were investigated. Perioperative complications were defined as complications identified within 90 days after surgery. The average observation time for esophageal stenosis was 10 weeks postoperative (6). This was categorized as a chronic complication and was not included in perioperative complications.

Thirty-day and 90-day mortality were estimated. Overall survival and recurrence-free survival rates were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

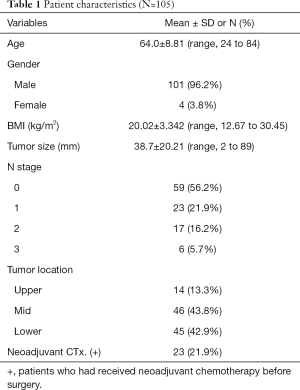

A total of 105 patients were included in this study. There were 25 times more male patients than female patients. The mean follow-up period was 64.0±8.81 (range, 24 to 84) months. Mean BMI (body mass index) was within normal range. More than 80% of cancers were located in the mid and lower esophagus, and 21.9% of patients underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy before surgery (Table 1).

Full table

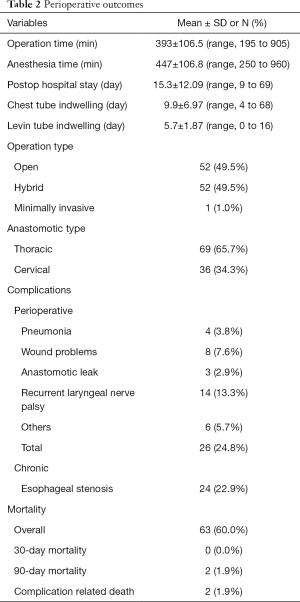

The perioperative complication rate was estimated as 24.8%. The most commonly observed short-term complication was recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, which was found in 14 patients (13.3%). Eight cases had operative wound problems, of which 4 cases required surgical intervention. Anastomotic leak was observed in 3 patients, and one required reoperation for treatment. Two cases of anastomotic leak were cured with only conservative management. Esophageal stenosis was diagnosed in 24 patients (22.9%). Perioperative results were summarized in Table 2.

Full table

Overall mortality rate during follow-up was 60.0% (63 patients). Among these patients, 24 died due to cancer progression. Nine patients died because of pneumonia, and complications related to death occurred in 2 patients. Thirty-day mortality was 0.0%. Two people died within 90 days, and both died of perioperative complications (fistula bleeding and aspiration pneumonia).

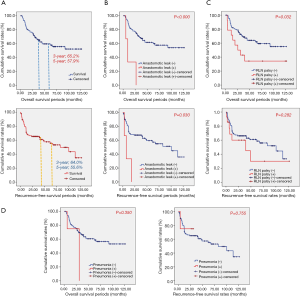

The 3-year overall survival rate was 65.2%, and 5-year overall survival was 57.9%. The 3-year recurrence-free survival rate was 64.0%, and 5-year recurrence-free survival rate was 55.6%. In survival analysis, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy was related to shorter overall survival (P=0.032); however, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy was not related to recurrent-free survival (P=0.282). Anastomotic leak was related with significantly lower overall and recurrence-free survival (P<0.000 and P=0.030, respectively, Figure 1). Esophageal stenosis was not related to overall survival or recurrence-free survival (P=0.057 and P=0.218, respectively).

Discussion

With 5-year survival rates of approximately 5–25%, the search for a cure of esophageal cancer is challenging (1,4). Treatment outcomes with combined mortality strategies are usually poor (4,7), likely due to diagnosis at advanced stages and the propensity for metastasis (1,8).

The efficient management strategies of esophageal cancer should include methods both for local control and systemic therapy. The best clinical outcomes are usually observed when the treatments are related with early stages (9,10), and the surgery could be an optimal choice for early stage esophageal cancer as a local control methods (11). However, it is often reluctant to be an option, mainly because of the associated considerable mortality and morbidities (4,12,13).

Surgeries for esophageal cancers are highly complex procedures involving two or three cavities (abdominothoracic or cervical abdominothoracic) (14). Surgery for esophageal cancers is reported to have a high morbidity rate of 30–50% even in large-volume surgical centers (3,12). Despite advances in surgical technologies such as minimally invasive esophagectomy and perioperative management including enhanced recovery after surgery, controversies remain regarding optimal surgical methods and postoperative care (4,13,14).

Numerous factors are associated with postoperative complications (4). Perioperative risk factors include age, nutritional condition, pulmonary function, smoking and alcohol habits, and neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Perioperative factors including the malignant potency of a tumor (size, location, local invasion, histological subtype, differentiation, or lymph node involvement), anesthesia time, amount of blood loss, and extension of surgical fields and postoperative factors such as postoperative respiratory muscle dysfunction, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, and lack of active pulmonary toilet are related to postoperative complications, mainly pulmonary problems (12,14).

Etiologic components may also have implications in mortality and morbidity after surgery. Large-volume centers continuously report lower mortality and morbidity rates than lower-volume centers (15). Trained surgeons with large-volume experience show better outcomes (16,17). Markar et al. reported a significantly increased incidence of in-hospital and 30-day mortality in low-volume than high-volume surgical unit (8.48% vs. 2.82%, and 2.09 vs. 0.71) (17). The surgical volume of our institute was close to upper threshold (9–10 cases per year) of low-volume hospital as the definition of the Marker’s reports, however, the mortality rates seemed quite similar to those of high-volume hospital. We thought that results were partly due to the surgeon’s proficiency.

Our study showed low 30-day mortality of 0.0%, 90-day mortality of 1.9%, and perioperative complication rates of 24.8%. Previous research reported mortality rates of 1–33% and complication rates of 30–60% (4,12,14). A previous study of Ivor Lewis operations showed 30-day mortality of 2% and perioperative complication rate of 67% (7).

Our study focused on esophagectomy with gastric conduit. There are various surgical methods for esophageal cancers, including transhiatal esophagectomy, two-or three-field esophagectomy, and left thoracoabdominal approaches. Incidence of complications varies according to approach and type of conduit (12). Less frequently used substitution organs, such as colon and jejunum, were excluded, as well as cases in combination with hypopharyngeal cancer.

Anastomotic leak related with conduit necrosis is a considerable source for morbidity and mortality (4,14). The incidence rates were reported up to 30%, depending on the localization of anastomosis (either cervical or thoracic) (18,19). This study comprised three cases of anastomotic leak, all of which occurred at cervical anastomosis. Two of cases were surgically, and one was medically treated. The patients who were medically treated died because of the fistula bleeding in anastomotic leak at postoperative 7 months. The rest patients who were treated with surgical methods died because of the cancer relapse at postoperative 3 and 18 months.

Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy may be a major contributor to significant morbidity and mortality, especially when associated with pulmonary complications (20). In our study, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy was significantly related to lower overall survival rates. Although not related to immediate postoperative (30-day) mortality, pneumonia was related to one perioperative death (90-day) and 6 cases of overall mortality.

Recent studies have reported minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) improves postoperative outcomes by reducing recurrent laryngeal nerve injury (21). Our study included only one case of minimally invasive esophagectomy and 52 cases of hybrid surgery (either VATS esophagectomy or laparoscopic gastric mobilization). Therefore, we could not show the influence of MIE on postoperative outcomes.

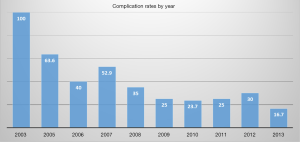

In our study, overall perioperative complications were estimated in 24.8% of cases. The incidence rates showed a tendency to decrease with time, and the complication rate in the year 2013 was 16.7% (Figure 2). This may be proof that surgeon experience is important for reducing complications.

Conclusions

We reviewed the long-term experience of a thoracic surgeon in esophagectomy for esophageal cancer treatment. Although still associated with high mortality and morbidity, esophagectomy with reconstruction using a gastric conduit is feasible if performed properly by an expert thoracic surgeon. Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy is the major factor determining overall survival outcome. Anastomotic leak also is an importance source affecting overall as well as recurrence-free survival rates. Minimally invasive esophagectomy may contribute to improved postoperative outcomes by reducing recurrent laryngeal nerve injury. However, further study is needed for definitive evidence.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: This study was retrospective review of previously existing data, not clinical prospective study and not related with any kinds of novel skills or drugs. The permission of IRB is thus not necessary for retrospective data review.

References

- Pennathur A, Gibson MK, Jobe BA, et al. Oesophageal carcinoma. Lancet 2013;381:400-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pakzad R, Mohammadian-Hafshejani A, Khosravi B, et al. The incidence and mortality of esophageal cancer and their relationship to development in Asia. Ann Transl Med 2016;4:29. [PubMed]

- van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2074-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- D'Amico TA. Outcomes after surgery for esophageal cancer. Gastrointest Cancer Res 2007;1:188-96. [PubMed]

- Flanagan JC, Batz R, Saboo SS, et al. Esophagectomy and gastric pull-through procedures: Surgical techniques, imaging features, and potential complications. Radiographics 2016;36:107-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park JY, Song HY, Kim JH, et al. Benign anastomotic strictures after esophagectomy: long-term effectiveness of balloon dilation and factors affecting recurrence in 155 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012;198:1208-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Griffin SM, Shaw IH, Dresner SM. Early complications after Ivor Lewis subtotal esophagectomy with two-field lymphadenectomy: risk factors and management. J Am Coll Surg 2002;194:285-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pennathur A, Farkas A, Krasinskas AM, et al. Esophagectomy for T1 esophageal cancer: outcomes in 100 patients and implications for endoscopic therapy. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;87:1048-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Enzinger PC, Mayer RJ. Esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med 2003;349:2241-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lepage C, Rachet B, Jooste V, et al. Continuing rapid increase in esophageal adenocarcinoma in England and Wales. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:2694-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ajani J, D'Amico TA, Hayman JA, et al. Esophageal cancer. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2003;1:14-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Atkins BZ, Shah AS, Hutcheson KA, et al. Reducing hospital morbidity and mortality following esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;78:1170-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Markar SR, Karthikesalingam A, Low DE. Enhanced recovery pathways lead to an improvement in postoperative outcomes following esophagectomy: systematic review and pooled analysis. Dis Esophagus 2015;28:468-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gockel I, Niebisch S, Ahlbrand CJ, et al. Risk and Complication Management in Esophageal Cancer Surgery: A Review of the Literature. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;64:596-605. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1128-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, et al. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 2003;349:2117-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Markar SR, Karthikesalingam A, Thrumurthy S, et al. Volume-outcome relationship in surgery for esophageal malignancy: systematic review and meta-analysis 2000-2011. J Gastrointest Surg 2012;16:1055-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim RH, Takabe K. Methods of esophagogastric anastomoses following esophagectomy for cancer: A systematic review. J Surg Oncol 2010;101:527-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Biere SS, Maas KW, Cuesta MA, et al. Cervical or thoracic anastomosis after esophagectomy for cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Surg 2011;28:29-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gockel I, Kneist W, Keilmann A, et al. Recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis (RLNP) following esophagectomy for carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2005;31:277-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Workum F, Berkelmans GH, Klarenbeek BR, et al. McKeown or Ivor Lewis totally minimally invasive esophagectomy for cancer of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorac Dis 2017;9:S826-S833. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Yi E, Bae MK, Jheon S. Analysis of postoperative outcomes for surgically resected esophageal squamous cell carcinoma reconstructed with gastric conduit. Shanghai Chest 2018;2:33.